Lesson 1. Patient Relations.

Lesson 2. The Adult Patient Care Unit.

Lesson 3. Advanced Principles of Patient Hygiene.

Lesson 4. Body Mechanics.

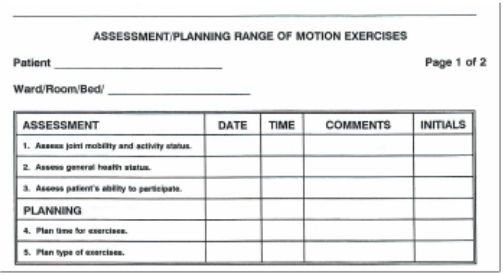

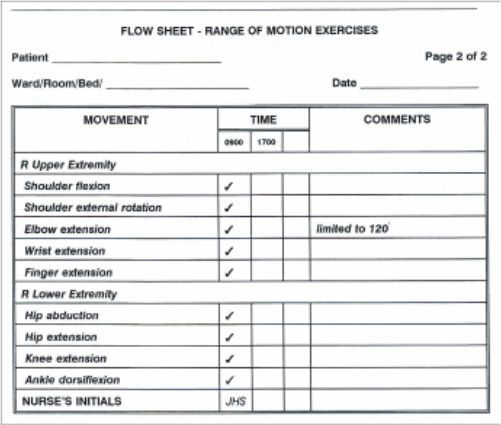

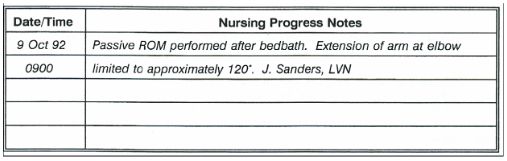

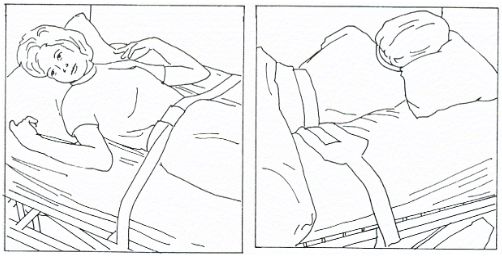

Lesson 5. Active and Passive Range of Motion Exercises.

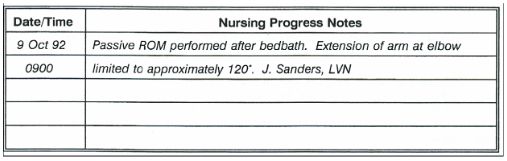

Lesson 6. Environmental Health and The Practical Nurse.

SECTION I. BASIC HUMAN NEEDS AND PRINCIPLES OF HEALTH

1-1. INTRODUCTION

Health is one of our most precious possessions. The preservation of health is met through the satisfaction of our basic human needs. Understanding the basic needs of people, therefore, is essential for the practical nurse in planning for and meeting the needs of the patient.

1-2. PRINCIPLES OF HEALTH

Definition of Health.

An individual's concept of health is a very personal thing. One person may consider himself to be healthy whenever he is not physically ill, while another may consider himself to be healthy only when he is emotionally and physically "at his best." A person's notion of health is influenced by a number of different factors or experiences, such as family background, self-concept, religion, past experiences, and socioeconomic status. It is important that you, as a practical nurse, keep this in mind when dealing with your patient's, as well as your own, feelings and interactions.

One person may consider himself to be healthy whenever he is not physically ill, while another may consider himself to be healthy only when he is emotionally and physically "at his best."

Total Health. Although the absence of disease and illness is, by anyone's definition, essential to good health, it is, by no means, the only factor. Total health includes all of the following aspects as well:

Social health. A sense of responsibility for the health and welfare of others.

Mental health. A mind that grows, reasons, and adjusts to life situations.

Emotional health. Feelings and actions that bring one satisfaction.

Spiritual health. Inner peace and security in one's spiritual faith.

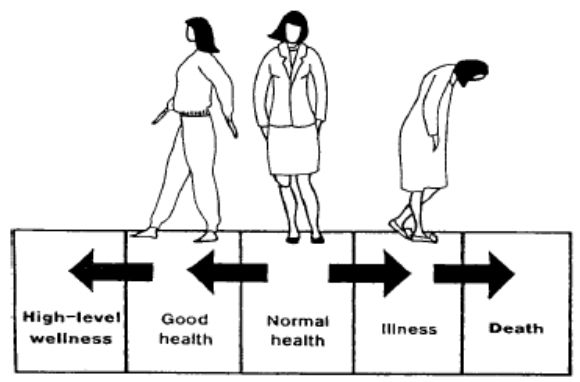

1-3. THE HEALTH-ILLNESS CONTINUUM

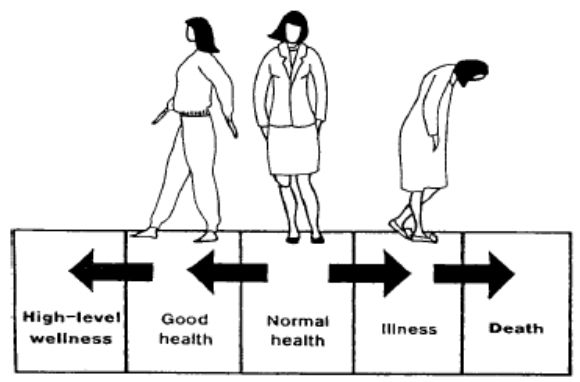

The individual's state of health is one of continual change. He moves back and forth from health to illness and back to health again. His condition is rarely constant. He may wake up feeling great, develop a headache mid-morning, and feel fine again by noon. The health-illness continuum (see figure 1-1) illustrates this process of change, in which the individual experiences various states of health and illness (ranging from extremely good health to death) that fluctuate throughout his life.

Figure 1-1. The health-illness continuum.

As we previously stated, health, just as life itself, is a process of continual change. And we must continually adapt to these changes in our lives in order to maintain good health and well-being. It is our adaptation or response to that change, rather than the change itself, that affects our health. For example, two students just found out about a big test tomorrow, for which they are completely unprepared. One student responds to this stressful situation (stressor) by going home, getting his books out, and starting to study. The other student breaks out into a sweat, and spends most of the evening fretting over this outrage and imagining what will happen to him if he doesn't pass the test. No doubt, this student is doing more damage to his health than is his friend. And, considering the time and energy he is expending on worrying (and not studying), he may experience even more stress when they receive their grades!

Adaptation and effective functioning, even in the presence of chronic disease, can be considered a state of wellness. A person may be in perfect physical condition, but feel too tired and "blue" to go to work, while his co-worker, a diabetic, is at work, functioning fully and accomplishing his job. Which of these two people is at a higher level on the health-illness continuum?

NOTE: Death occurs when adaptation fails completely, and there is irreversible damage to the body.

1-4. ADAPTING TO CHANGE

A person may be in perfect physical condition, but feel too tired and "blue" to go to work, while his co-worker, a diabetic, is at work, functioning fully and accomplishing his job.

The individual's state of health is determined by the ability to adapt to changes in the following dimensions:

Developmental--changes in a person's behavior and ability, which are associated with increasing age.

Psychosocial--the development of the personality, social attitudes, and skills.

Cultural--changes in or development of beliefs and values held by the individual's family or culture.

Physiological--changes in body function.

1-5. POSITIVE HEALTH HABITS

Regardless of one's definition of health, the individual who practices the following positive health habits on a regular basis is certainly at an advantage.

A balanced diet with adequate caloric intake.

Efficient elimination.

Regular exercise.

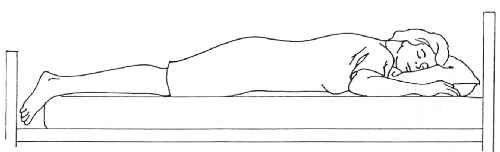

Adequate sleep, rest periods, and relaxation periods.

Regular medical checkups.

Regular dental checkups.

Maintenance of good posture.

Good grooming habits.

SECTION I. BASIC HUMAN NEEDS AND PRINCIPLES OF HEALTH

1-6. CATEGORIES OF BASIC HUMAN NEEDS

Physical Needs. These are closely related to body functions and are sometimes referred to as primary or physiological drives. Physical needs include:

Food.

Water.

Oxygen.

Elimination.

Clothing and shelter for body warmth and protection.

Activity, or sensory and motor stimulation, including sex, physical exercise, and rest. Emotional Needs. Emotional needs are closely interwoven with physical needs and are met in interaction with significant others.

They include:

Love, including approval and esteem.

Importance, including recognition and respect. NOTE: This applies to the patient's perception of the nurse's feelings toward him. For example, if your patient feels that you do not approve of or respect him, he may become very demanding, or he may withdraw and not cooperate with your efforts to make him healthy again.

Adequacy, including self-sufficiency and the need to be needed and wanted.

Productivity, including work and creative pursuits.

NOTE: Remember that all human behavior is aimed toward the satisfaction of basic human needs.

Social Needs. Social needs grow out of the culture and society of which one is a member. They include:

Identification or belonging.

Education or learning.

Recreation or play.

Religion or worship.

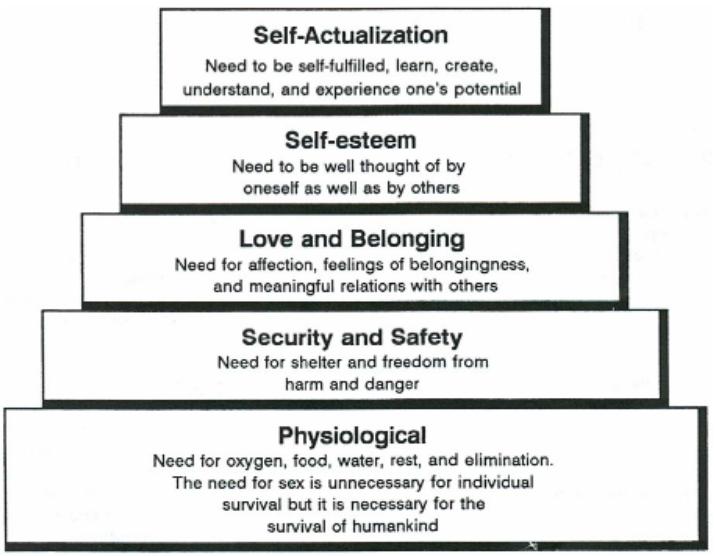

1-7. MASLOW'S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

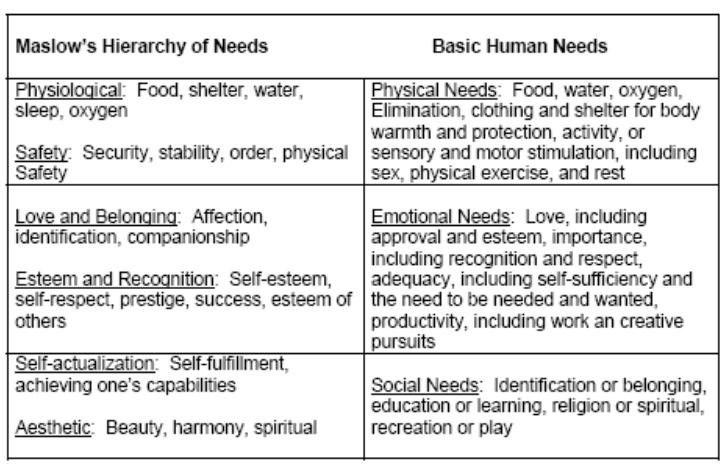

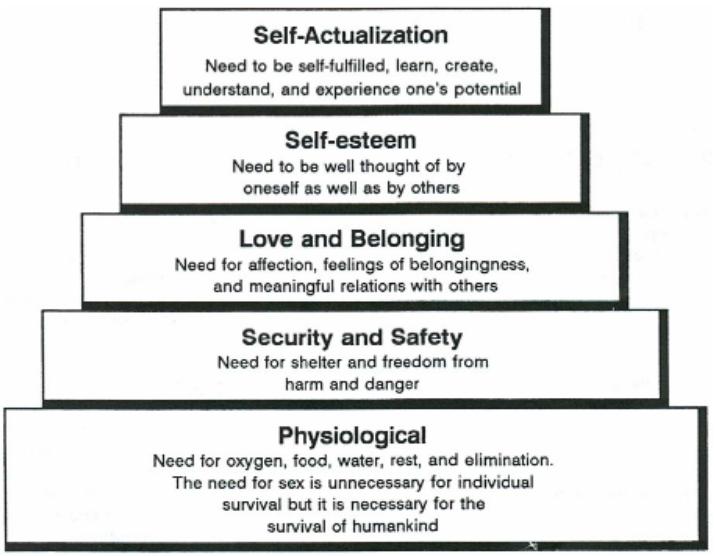

Psychologist Abraham Maslow defined basic human needs as a hierarchy, a progression from simple physical needs to more complex emotional needs (see figure 1-2).

Types of Needs.

Physiological--food, shelter, water, sleep, oxygen.

Safety--security, stability, order, physical safety.

Love and belonging--affection, identification, companionship.

Esteem and recognition--self-esteem, self-respect, prestige, success, esteem of others.

Self-actualization--self-fulfillment, achieving one's own capabilities.

Aesthetic--beauty, harmony, spiritual.

Relationship Between Levels of Needs.

According to Maslow, the basic physiological needs related to survival (food, water, etc.) must be met first of all.

These basic physiological needs have a greater priority over those higher on the pyramid. They must be met before the person can move on to higher level needs. In other words, a person who is starving will not be concentrating on building his self-esteem. A patient in severe pain will not be concerned with improving his interpersonal relationships.

Generally speaking, each lower level must be achieved before the next higher level(s) can be focused upon.

1-8. COMPARISON OF BASIC HUMAN NEEDS AND MASLOW'S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

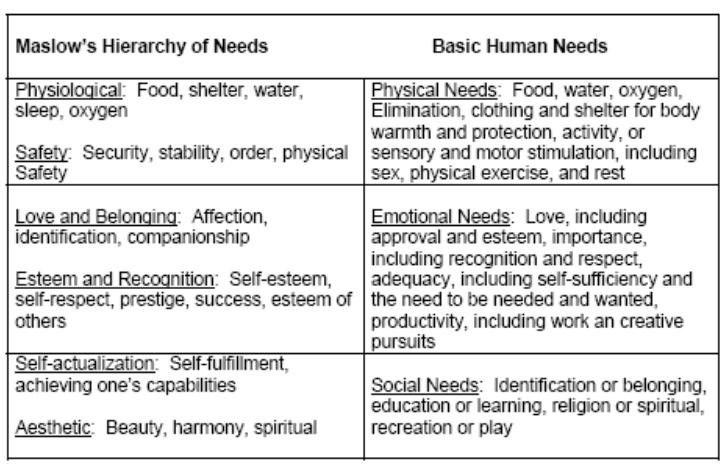

The categories of Maslow's hierarchy are closely related to the basic human needs discussed in paragraph 1-6. Table 1-1 contains a comparison.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Basic Human Needs

Table 1-1. Comparison of basic human needs and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Physical needs are roughly equivalent to Maslow's physiological and safety needs.

Emotional needs are roughly equivalent to Maslow's love and belonging and esteem and recognition needs.

Social needs are roughly equivalent to Maslow's self-actualization and aesthetic needs.

1-9. CLOSING

Remember that human needs are not constant; they are fluid and changing with first one, then another, taking priority. What may start as a basic need for food can take on social and personal significance. Your care plan as well as your patience are aimed toward the satisfaction of the patient's needs. He has common needs because he is a person; he has individual needs because he is unique; he has special needs because he is sick. The Practical Nurse supplies the help that is required to meet the patient's needs during the stressful periods of hospitalization and recuperation.

SECTION II. COMMUNICATION SKILLS

1-10. INTRODUCTION

If you were to try to explain the process of human interaction, you might define it as a huge and very complex communication system. Nevertheless, it is essential that you develop and maintain an understanding of the methods and skills of communication in order to meet the needs of the patient. The quality of care you can provide is, in many ways, dependent on the quality of communication that exists between you and your patient. Through your direct contact, the patient must perceive your intentions of support and your positive expectations. You must accurately assess the patient's physical and emotional symptoms. Communication has only taken place if the message being sent was accurately received.

1-11. PURPOSES OF COMMUNICATION

Major Purpose. To send, receive, interpret, and respond appropriately and clearly to a message, an interchange of information.

Supportive Purposes.

To correct the information a person has about himself and others.

To provide the satisfaction or pleasure of expressing oneself.

1-12. ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF THE HUMAN COMMUNICATION SYSTEM

The essential components of communication are:

Sender--the originator or source of the idea.

Message--the idea.

Channel--the means of transmitting (either verbally or nonverbally) the idea.

Receiver--someone to receive and interpret the message.

Feedback--the response to the message.

The quality of care you can provide is, in many ways, dependent on the quality of communication that exists between you and your patient.

1-13. VERBAL AND NONVERBAL METHODS OF COMMUNICATION

Verbal Communication. Verbal communication refers to the use of the spoken word to acknowledge, amplify, confirm, contrast, or contradict other verbal and nonverbal messages.

Nonverbal Communication. Nonverbal communication refers to an exchange of information without the exchange of spoken words (facial expressions, body language, etc.).

Essential Relationship. Verbal communication is always accompanied by nonverbal expression. Even no expression tells the other person something.

1-14. METHODS OF NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

Rapport. The harmonious feeling experienced by two people who hold one another in mutual respect, acceptance, and understanding.

Empathy.

Empathy is that degree of understanding, which allows one person to experience how, another feels in a particular situation.

Remember that actions speak louder than words. A person will generally pay more attention to what you do than what you say.

Body Language. Remember that actions speak louder than words. A person will generally pay more attention to what you do than what you say. Think about the following nonverbal messages and what they might reveal.

Facial expressions (smile, frown, blank look, grimace).

Gestures/mannerisms (fidgeting, toe tapping, clenched fists).

Eye behaviors (avoiding eye contact, staring, wide eyes).

Use (and avoidance) of touch or physical contact.

Posture (erect, slouching, leaning toward/away from someone).

Walk.

Silence. Silence can be an extremely effective communication tool. It can be used to express a wide range of feelings.

Silence can be used to communicate the deepest kind of love and devotion, when words are not needed.

Silence can be a cold and rejecting sort of punishment, the "silent treatment" received for coming home late or forgetting an anniversary.

Silence can be used in an interview or conversation to encourage the other person to "open up." Conversely, it can be used to intentionally create anxiety and discomfort in the other person.

Listening. As a patient speaks, think about what he must be feeling. Sometimes, as a listener, you must cut through layers of words to get to the real message. You must read between the lines. Pick up the underlying meaning of the message (intent); don't rely entirely upon the obvious or superficial meaning (content).

1-15. GUIDELINES FOR COMMUNICATING WITH PATIENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES

Convey to the patient and family that they are important to you and that you want to help them. There are many ways to do this; you must do what is comfortable and natural for you. However, there are some things everyone can do.

Convey honesty and trustworthiness.

Try not to overwhelm the patient with embarrassing or personal questions. When it is necessary to ask personal questions, explain why and keep it short and matter-of-fact.

Don't make promises you can't keep. If you say you are going to do something, make every effort to do it or see that it gets done.

Try to be there when you say you will. If you are late, explain why.

Communicate with each patient as an individual. (This is especially important in a hospital setting, where patients often experience a loss of identity.) In order to do so, you must try to get to know the patient. Listen to him. Put yourself in his place.

Accept and respect the patient despite the symptoms of his illness.

1-16. TECHNIQUES FOR COMMUNICATING WITH PATIENTS

Sit down when speaking to the patient. Although you probably have dozens of things you need to be doing at that moment, try to relax.

Establishing the Setting.

Provide a comfortable environment (lighting, temperature, furnishings).

Establish a relaxed, unhurried setting.

Sit down when speaking to the patient. Although you probably have dozens of things you need to be doing at that moment, try to relax. Don't stand at the doorway or sit on the edge of your seat, as if you are preparing to jump and run as soon as you can get away.

Face the speaker and maintain eye contact.

Provide for privacy.

Avoid interruptions and other distracting influences.

Verbal Communication Skills.

Let the patient do the talking.

Keep questions brief and simple.

Use language that is understandable to the patient. Avoid acronyms and medical/nursing jargon if the patient is nonmedical.

Ask one question at a time. Give the patient time to answer.

Clarify patient responses to questions, not just for your own use, but also to let the patient know that you are listening (be sure you really are) and that you understand.

Avoid leading questions. You want the patient to tell you what he is feeling, not what he thinks you want to hear. So avoid putting words in his mouth. For example, it might be better to ask, "How are you feeling?" rather than "I suppose you're feeling rested after your nap."

Avoid how or why questions; they tend to be intimidating.

Avoid the use of cliché statements like, "Don't worry; it'll be all right." or "Your doctor knows best."

Avoid questions, which require only a simple "yes" or "no" response. You want to encourage the patient to talk to you.

Avoid interrupting the patient. If you need to ask a question, wait until he has completed his thought.

You can reflect on what you think the patient is feeling. "It sounds like you're concerned about your family." or "I don't think you're very happy about this."

Interviewing Techniques. The following terms represent skills often used to foster better communication. Before using these techniques, remember that you must do what feels comfortable and natural to you. Even though you may have the best of intentions, if you do not sound sincere, what are the chances of someone really opening up to you? Also, keep in mind that your patients are individuals; if you sense that a particular patient may not respond well to a certain technique, you are probably right.

Reflection. Repeating content or feelings. You might simply repeat what the patient has said, to give him time to mull it over or to encourage him to respond. Or, and often more effectively, you can reflect on what you think the patient is feeling. "It sounds like you're concerned about your family." or "I don't think you're very happy about this." By reflecting on his feelings, you may be encouraging him to talk about something he may have been hesitant to bring up himself. Or you may be helping the patient to identify his own feelings about something.

Restating. Rephrasing a question or summarizing a statement. "You're asking why these tests are needed?" or "In other words, you think you're being treated like a child."

Facilitation. Occasional brief responses, which encourage the speaker to continue. A nod of the head; an occasional verbal cue, such as "go on" or "I see;" and maintaining eye contact throughout the conversation all imply that you are listening and that you understand.

Open-ended questions. Questions that encourage the patient to expound on a topic. If you want to encourage the patient to speak freely, you might ask "How are you feeling?" rather than "Are you in pain?"

Closed-ended questions. Questions, which focus the patient on a specific topic. If you want a short, straight answer, ask a question which will allow only for a direct response, such as "When was your accident?" or "Do you have pain after eating?"

Silence. A quiet period that allows a patient to gather his thoughts. Of course, this would be an occasional practice, used when you feel that the patient could use a little time to think about his response to a question or just to think.

Broad openings. A few words to encourage the patient to further discuss a topic; for example, "and after that..." or "you were saying..."

Clarification. Statements or questions that verify a patient's concern or point. "I'm a bit confused about...Do you think you could go over that again please?"

1-17. THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION

Practicing therapeutic communication is in many ways simply developing a good bedside manner. When your patient asks you a question or discusses something with you, be careful to respond in a helpful and caring manner. By encouraging the patient to speak up, you are probably helping him/her to decrease his level of stress and thereby his recovery time.

Study the techniques discussed in paragraphs 1-15 and 1-16. Become familiar enough with them so that they become a natural part of your conversations.

When your patient communicates with you, you must be able to correctly observe, evaluate, and respond. Your knowledge, understanding, and skill in human relations will enable you to do so.

1-18. CRITICAL ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE THERAPEUTIC COMMUNICATION

Be able to decipher the patient's message. Get to know the patient well enough to discover the underlying meaning (intent) of his/her communication. Be alert and perceptive enough to pick up the correct message. Many people feel uncomfortable talking about their feelings, especially if they are trying to be "good patients." Learn to "read between the lines."

When communicating with patients, each Practical Nurse has to find the ways that are the most effective for the people and circumstances concerned.

Be realistic in your relationships with people; avoid making assumptions or judgments about your patients' behavior. If you have negative thoughts about something a patient says or does, try to keep in mind that he is an adult, responsible for making his own decisions. You do not want him to feel he must conceal anything from you. You want him to see that you will accept him for what he is; you will allow him his own identity.

Be emotionally mature enough to postpone the satisfaction of your own needs in deference to the patient's. Find sources other than the therapeutic relationship to meet your own needs.

1-19. NURSING INTERVENTION WITH PATIENTS WITH SPECIAL COMMUNICATION NEEDS

Blind Patients.

Always speak to the patient when you enter the room so he will know who is there.

Speak directly to the patient; do not turn your back.

Speak to the patient in a normal tone of voice; he is blind, not deaf.

Speak to the patient before touching him/her.

Offer to help with arrangements for patients who may enjoy hearing tapes or reading Braille literature.

Deaf Patients.

Look directly at the patient when speaking with him/her.

Do not cover your mouth when speaking because the patient may read lips.

If the patient does not lip-read, charts with pictures may be used, or simply writing your questions or comments on a piece of paper may be helpful.

Charts with hand signs are available at the local society for deafness and/or hearing preservation.

Patients Speaking a Foreign Language.

Obtain a translator if possible. The Red Cross or the Patient Administration Division (PAD) may be of assistance.

Have a chart with basic phrases in English and the foreign language.

Consider using charts with pictures.

1-20. CLOSING

When communicating with patients, each Practical Nurse has to find the ways that are the most effective for the people and circumstances concerned. If the Practical Nurse tries to express care and concern for the patient and can communicate well verbally and non verbally, the nurse-patient relationship will thrive.

SECTION III. REACTION TO STRESS AND HOSPITALIZATION

1-21. INTRODUCTION

The patient who is entering a hospital is under many emotional pressures. Fear of death, disfigurement, pain, or a prolonged illness, and loss of control of the surrounding environment are just a few of the emotional concerns being faced. People react to stress in many ways. The Practical Nurse must be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of stress and identify the coping mechanisms being utilized by the patient in order to provide effective nursing care.

1-22. FACTORS INFLUENCING WHETHER A PERSON WILL SEEK OR AVOID PROFESSIONAL HELP

Some of the factors that influence a person seeking or avoiding professional help are:

The degree and extent of symptom distress.

Expectation of return to health if treatment is instituted.

Fear of diagnostic and treatment procedures.

Fear of discovery of serious illness.

The self-concept that one is always healthy.

1-23. FACTORS CAUSING STRESS IN THE HOSPITAL

Some of the factors that cause stress in the hospital are:

Unfamiliarity of surroundings.

Having strangers sleep in the same room.

Having to eat cold or tasteless food.

Being awakened in the night by the nurse.

Loss of independence.

Having to eat at different times than usual.

Having to wear a hospital gown.

Not having the call light answered.

The patient who is entering a hospital is under many emotional pressures.

Separation from spouse.

Separation from family.

Financial problems.

Isolation from other people.

Having an unfriendly roommate.

Not having friends visit.

Having staff in too much of a hurry to talk, or more importantly, listen.

Lack of information.

Not having questions answered by staff members.

Having nurses or doctors who talk too fast. Nervousness and preoccupation often make it difficult to fully concentrate on what is being said. Needless to say, patients often have plenty on their minds, so it is crucial that you explain things patiently and slowly and be prepared to repeat instructions and explanations. Do not assume that because you have explained something once, your job is done.

Not knowing the reasons for (or the results of) treatments.

Threat of severe illness.

Fear that appearance will be changed after hospitalization.

Being hospitalized after an accident and suspecting the worst.

Thinking he/she may have cancer.

Problems with medications.

Having medications cause discomfort (that is., chemotherapy).

Not getting relief from pain.

Not getting pain medication when needed.

1-24. STAGES OF THE ILLNESS EXPERIENCE

During Recovery, Rehabilitation or Convalescence, the patient goes through a process of resolving his/her perceived loss or impairment of function.

Denial or Disbelief in Being Ill.

Patient may avoid, refuse, or even forget needed care.

Patient may appear to flee toward health in trying to escape illness.

Acceptance of Being Ill.

Becomes dependent on health care personnel.

Focuses attention on symptoms and the illness.

Gradually becomes less dependent.

Recovery, Rehabilitation, or Convalescence.

May be a short or long period, depending on how much the patient's life-style must change as a result of the illness.

Patient goes through a process of resolving his/her perceived loss or impairment of function.

1-25. EMOTIONAL RESPONSES TO ILLNESS AND HOSPITALIZATION

Fear.

An emotional response characterized by an expectation of harm or unpleasantness.

Usually associated with behavior that attempts to avoid or flee a threatening situation.

Patient is usually aware of the specific danger and has some understanding into the reasons for the fear. Common indications of fear include:

Tachycardia (rapid heart rate).

Dry mouth.

Constipation.

Hypertension.

Increased perspiration.

The "fight or flight" reaction (alertness and readiness for action in order to avoid or escape harm).

Anxiety.

An emotional response characterized by feelings of uneasiness and apprehension of a probable danger or misfortune.

Patient who is anxious usually is unaware of the cause of the anxiety.

Behaviors are similar to those seen with the fear, but are not usually as dramatic.

Because the patient does not know its specific cause, he/she usually focuses on the physiologic symptoms of anxiety, to include:

Fatigue.

Insomnia.

Diarrhea or constipation.

Urgency.

Nausea.

Anorexia.

Excessive perspiration.

Stress.

A state of strain or tension.

Occurs in situations, which require an increased and often prolonged effort to adjust.

Any factor that disturbs the physical, psychological, or physiological homeostasis of the body may be stressful.

As with fear, the body tries to rid itself of the factor causing the stress.

Physical signs of stress include:

Ulcers.

Hair loss.

Insomnia.

Over Dependency or Feelings of Helplessness.

Over dependency is a response characterized by feelings of helplessness while trying to search for help and understanding (to an extent beyond what is considered normal).

Helplessness is a response characterized by feelings of being unable to avoid an unpleasant experience.

While healthy people may show some degree of dependence on others during illness, this dependence often increases to the point of being harmful to the patient.

The over dependent patient may be fearful or angry.

1-26. CLOSING

There are as many reactions to illness as there are patients. Your kindness and understanding will help your patient to go through the hospitalization experience with a minimum of stress and anxiety.

SECTION IV. TRANSCULTURAL FACTORS INFLUENCING NURSING CARE

1-27. INTRODUCTION

Transcultural nursing refers to the nursing care of all patients, taking into consideration their religious and sociocultural backgrounds. There are many variables to consider in giving nursing care to a person of a race, religion, or culture different from your own. Respect for the patient, however, is something all aspects of transcultural nursing have in common.

1-28. MAJOR FACTORS IN TRANSCULTURAL NURSING

Nutrition and dietary practices.

Beliefs about illness, its causes and cures.

Disorders specific to a particular group, such as the high incidence of sickle cell anemia among the Blacks.

Specific anatomical characteristics (e.g, stature, skin tone, hair texture).

Religious beliefs about illness and death.

1-29. VARIABLES RELATING TO THE TRANSCULTURAL ASPECTS OF NURSING

Some of the factors are:

Cultural background of the nurse; differences and similarities between the patient and the nurse.

Definition of health and illness accepted by a specific culture; concepts relating to the causes of illness and injury.

Folk medicine practices.

Attitudes toward health care, relationships, and interactions (e.g., personal space, eye contact).

Economic level of the patient and family (socioeconomic status).

Environmental factors and related disorders (e.g., ghetto living, lead poisoning).

Specific names and terms related to the illness or disorder (e.g.,"bad blood," "mal ojo"); use of slang.

Language differences between the health care staff and the patient and family.

Modesty and concept of the human body.

Reactions to pain, aging, and death.

Attitudes about childbirth, abortion, sexual expression, children born to unmarried parents, and homosexuality.

Attitudes about mental illness and retardation.

Diets in relation to religious and cultural practices; dietary taboos.

Attitudes about physical appearance and obesity; adaptation to special therapeutic diets.

Importance of religion and religious practices.

Religious practices in illness and death; specific prohibitions.

Group identity; importance and type of family structure; cohesiveness within the group; traditional roles of men and women.

Blacks and Raza/Latino cultures have long used roots, potions, and herbs for treating illnesses.

"Visibility" of ethnic background (that is, Black, Oriental).

Disorders specific to a cultural group (that is, Tay-Sachs, sickle cell anemia).

Attitudes about school; educational level and aspirations of most members of the group.

Predominant occupations within the group; role models.

"Americanization" of younger members.

Numbers of people belonging to that group in the same geographic area as the health care facility.

Prejudices within a cultural group relating to other members of the same group.

Stereotypes about other cultural/ethnic groups.

Mixed families (mixed races, religions, or cultural backgrounds).

1-30. SOCIOCULTURAL BELIEFS ABOUT ILLNESS, ITS CAUSES, AND CURES

Examples of Differences in Beliefs About the Causes of Illness.

Japanese Shintoist.

Man is inherently good.

Illness is caused when the person comes into contact with pollutants, such as blood or a corpse.

Native Americans. Native Americans follow these three concepts:

Prevention.

Treatment.

Health maintenance.

The person's health is defined in terms of the person's relationship with nature and the universe.

Examples of Differences in Treatment of Disorders.

Blacks and Raza/Latino cultures have long used roots, potions, and herbs for treating illnesses.

Filipinos and Raza/Latino groups believe that:

Hotness and coldness, wetness and dryness, must be balanced to be healthy.

Certain illnesses are hot or cold, wet or dry.

Certain foods and medications, classified as hot or cold, are added or subtracted to bring about a balance of humors or to fight off "hot" or "cold" illnesses.

Copper bracelets are worn by some groups as a preventive or cure for arthritis.

There are many variables to consider in giving nursing care to a person of a race, religion, or culture different from your own.

Other Cultural Influences to Consider When Planning Nursing Care.

The nurse should take into consideration the needs of people who practice folk healing. The folk healer (curandero in Spanish) should be allowed to see the patient.

South Americans often wear chains to drive away evil spirits. The nurse should not remove these unless it is absolutely necessary.

Native American women are not likely to seek early prenatal care. They believe that pregnancy is a natural, normal process; a clinic or a hospital is associated with illness.

Many Latino patients believe that it is dangerous to bathe immediately after delivery. The nurse must remember this during postpartum care.

Many cultural groups, such as Native Americans and Southeast Asians, believe that it is improper or impolite to look someone in the eye when speaking to him/her.

SECTION IV. TRANSCULTURAL FACTORS INFLUENCING NURSING CARE

1-31. RELIGIOUS BELIEFS ABOUT ILLNESS AND DEATH

The Jewish Religion.

Practices.

Dietary practices vary among Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Jews.

The patient should be asked if/how he/she observes the Kosher dietary laws.

The head nurse or dietician should be notified so that the dietary practices can be considered when meals are prepared and served.

The Jewish person is expected by the culture to be independent and self-reliant; and emphasis is placed upon responsibilities and obligations to God.

All practicing Jews observe Saturday as the Sabbath.

The most important Jewish holidays are Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, and Passover.

The patient may wish to see the Rabbi (spiritual leader).

Circumcision of male infants is generally a religious ceremony and is sometimes performed at the hospital.

Nursing implications.

Although it is usually not possible to serve Kosher meat in a nonsectarian hospital, the nurse can be sure not to serve meat and dairy foods together or pork to an Orthodox Jewish patient.

Allow the patient to be as independent as possible and make as many of his/her own decisions as possible.

Be especially observant for indications that a patient needs pain medications because he/she may not tell you if he/she needs them. These indications may be:

Restlessness.

Diaphoresis (perspiration, often perfuse).

A distressed facial expression.

Withdrawal.

You may have to help arrange for a place in the hospital to have a male child circumcised.

Arrange for a Rabbi to visit the patient on Saturdays or special holidays.

The Protestant Faith.

Practices.

There are many denominations in the Protestant faith. Most denominations recognize two sacraments: Baptism and Communion.

A person may be baptized by a layperson, such as a nurse, in an emergency.

Christmas and Easter are the most important Christian holidays for Protestants, as for other Christians.

Nursing implications.

Ask the patient if he/she would like a visit from a Minister or other member of the church.

In the event of an emergency in which an infant or adult may become critical and/or die, the nurse may baptize the patient, if asked, or may do it if he/she (the nurse) thinks it may be comforting to the patient and/or family.

Inquire about any specific dietary or religious practices and provide this information to the appropriate person.

The Roman Catholic Faith.

Practices.

The Roman Catholic Church considers Baptism, Confession, Holy Communion, and the Sacrament of the Sick as basic sacraments of the Church.

During a long illness, a Catholic patient usually wants a priest to hear confession and to give communion. At such times, the nurse should provide as much privacy as possible.

Death is viewed from three aspects:

Visible reaction: emphasis on faith in God.

Fear of dying and of judgment: trying to get life in order.

Desire for death: emphasis on returning to God.

The last rites of the Church (Sacrament of the Sick)

A vital part of the Catholic faith.

Comforts both the patient and the family members.

Easter and Christmas are the most important holidays in the Roman Catholic faith.

Many Catholics abstain from or restrict their intake of meat during Lent, which is the 40-day period from Ash Wednesday to Easter. Some have maintained the custom of abstaining from meat on Fridays.

Many Catholics abstain from or restrict their intake of meat during Lent, which is the 40-day period from Ash Wednesday to Easter. Some have maintained the custom of abstaining from meat on Fridays.

Nursing implications.

In case of an emergency or impending death, a member of the nursing staff may perform a Baptism.

If a patient is brought into the hospital unconscious or in a serious condition and found to have a rosary, Catholic medal, or identification card indicating that the patient is Catholic, a priest should be called so the patient may have the Sacrament of the Sick.

If a patient wishes to abstain from meat because of a religious holiday, inform the dietician or head nurse so that arrangements can be made.

During important holidays, the patient may want to see a priest and/or attend Mass.

Christian Science.

Practices.

Christian Scientists do not permit surgery or many other forms of medical care.

They believe that all illness is mental in origin.

They believe that illness can be cured by appropriate mental processes.

Treatment consists of prayer and counsel for the sick person; healing is carried out by certified practitioners.

Healing is highly intellectual.

There is no formal clergy.

Nursing implications.

Because surgery or other medical care is not permitted, often legal intervention must be obtained in order to give care in an emergency situation.

Because there is no formal clergy, arrangements may have to be made to have other church members visit the patient.

The Latter Day Saints.

Practices.

Mormons are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

They believe in the laying on of hands in treating deformities.

They do not use tobacco; drink stimulants (such as coffee, tea, or cola drinks) or alcoholic beverages; or consume chocolate.

Nursing implications.

Inform the dietician or Head Nurse of the patient's dietary requirements.

Ask the patient if he/she has any particular religious practices he/she wishes to follow and adhere to them if possible.

The Adult Patient Care Unit

2-1. INTRODUCTION

The patient care unit is the area of the hospital in which the patient receives medical and nursing care and treatment as well as the place in which he/she lives during his/her hospital stay. It must be maintained as a safe, pleasant, clean, and orderly environment for the patient's physical and mental well being. Constant effort is needed to achieve and maintain the necessary high level of order and sanitation.

2-2. FURNITURE COMPRISING THE PATIENT BASIC UNIT

Furniture for the patient basic unit includes:

Bed.

Bedside cabinet.

Overbed table.

Chair.

Hospital Bed Arrangement in

Labor and Delivery

2-3. EQUIPMENT/ARTICLES NECESSARY FOR PROVIDING BASIC NURSING CARE

The following are provided to the patient:

Linens.

Bed linens.

Towels.

Washcloths.

Blankets.

Toilet Equipment.

Wash basin.

Soap dish.

Emesis basin.

Bedpan.

Urinal.

Toilet paper.

Other Articles.

Water pitcher.

Glass.

Call button.

Disposable facial tissues.

Emesis Basin

2-4. GUIDELINES FOR BED-MAKING

a. Gather all the required linen and accessories before making the bed.

Sheets.

Pillowcases.

Blankets.

Bedspread.

Extra pillows.

b. Avoid shaking the linen to prevent the spread of microorganisms and dust particles.

c. Avoid placing linens, clean or dirty, on another patient's bed.

d. Do not place dirty linen on the floor.

e. Do not hold dirty linen against your uniform.

f. Always use good body mechanics; raise the bed to its highest position to make bed-making easier.

g. Stay on one side of the bed until it is completely made; then move to the other side and finish the bed. This saves time and steps.

h. Observe the patient and document any nursing observations.

Check for areas of redness that may lead to decubiti formation.

Note tolerance of activity level while out of bed.

Note observations about the physical and emotional status of the patient.

Note any patient teaching or reinforced teaching given and the patient's response.

Check for drainage, wetness, or other body fluids and record observations.

2-5. METHODS OF BED-MAKING

Video showing cleaning of a bed

(1MB)

Video showing making of a bed

(4 MB)

After wrapping the sheet over the top of the mattress, lift the edge at a 45 degree angle.

Tuck the end of the sheet under the mattress.

Then fold the grasped portion of the sheet down and slide it under the mattress, creating a neat and durable mitered corner.

Unoccupied (Closed) Bed. An unoccupied bed is one that is made when not occupied by a patient.

Raise the bed to a comfortable working height, if adjustable.

Lower siderails, if present.

Remove pillows and pillowcases. Set the pillows aside in a clean area.

Fold and set the blankets and spreads aside (to be reused).

Loosen the linen along the edges of the bed, and move toward the end of the bed.

Wash the mattress if necessary, turn the mattress to the opposite side if necessary, and replace the mattress pad as needed. Observe the mattress for protruding springs.

Place the bottom sheet.

Flat sheet.

Position evenly on the bed.

Miter the corners at the top of the bed. Lift the mattress slightly, then stretch and tie the ends of the sheet together beneath the mattress. Repeat these steps for the bottom of the bed.

Stretch and tuck the free edges at the sides.

Fitted sheet.

Fit the sheet on the lower edges of the mattress first. Then lift the mattress and fit the sheet on the top edges of the mattress.

Stretch and tuck the free edges at the sides.

Place a draw sheet on the center of the bed, if it is needed.

Tuck in the free edge on one side.

Stretch the draw sheet from the opposite side and tuck in the free edge.

Place the top sheet, blanket (if used), and bedspread.

Position evenly on the bed.

Miter the bottom corners, tucking all three parts together.

Leave the loose ends free.

Fanfold the top linen back to the foot of the bed.

Place a clean pillowcase over the pillow and place it at the head of the bed.

Invert the pillowcase over one hand so the inner back seam is visible.

Grasp the edge of the pillow with one hand holding the pillowcase at the seam.

Use the opposite hand to guide the pillowcase over the pillow.

Adjust the bed to its lowest position, if adjustable.

Reposition the head up slightly, if the patient prefers.

Raise the siderail opposite the side of the bed where the patient will enter.

Occupied (Open) Bed. An occupied bed is one that is made while occupied by a patient.

Wash your hands.

Identify the patient, explain the procedure, and be sure you will have the patient's cooperation.

Check the condition of the bed linens to determine which supplies you will need.

Provide for the patient's privacy (throughout the procedure).

Obtain the articles of linen that you will need.

Place the bath blanket over the patient and the top cover.

Loosen the top bedding from the foot of the bed and remove it. If possible, have the patient hold the bath blanket while you pull the top covers from under it from the foot of the bed.

Move the mattress to the head of the bed.

Move the patient to the distal side of the bed.

Make the bed on one side.

Move or turn the patient to the clean side of the bed, and finish making the bed on the opposite side. Place the clean linen on top, and remove the bath blanket.

Attach the patient's signal cord within reach.

Provide for the patient's safety and comfort.

Tidy the room.

Anesthetic, Surgical, or Post-Op Bed. This is a bed that is prepared to receive a patient from the operating room.

Gather all needed supplies:

Large sheets (2).

Drawsheet (1) or an additional large sheet.

Blanket.

Pillow(s).

Pillowcase(s).

Towel.

Chux ®, if drainage is anticipated.

Make the bed as though you are making an unoccupied bed, except that the top sheet and blanket are not tucked under the mattress at the foot of the bed, and the corners are not mitered.

Fanfold the top covers to the side or to the foot of the bed.

Place a towel or disposable pad (Chux ®) at the head of the bed. This is intended to protect the sheet if the patient should vomit.

It is a good idea to place a drawsheet on the bed because it can be used to move the patient more easily.

Place the pillow(s) on a chair near the bed or in an upright position at the head of the bed.

Leave the bed in the high position.

Lock the brakes on the bed.

Move the furniture away from the bed to allow for easier access to the bed for the recovery room stretcher and personnel.

Make certain an emesis basin is readily available and suction is available where indicated.

Keep Chux ® available to use if necessary.

Bed in Low Position

Bed in High Position

2-6. TERMINAL CLEANING OF THE PATIENT CARE UNIT

Definition.

The sanitation of the bed, bedside cabinet, and general area of the patient care unit with a detergent/germicidal agent after the patient is discharged or transferred from the nursing care unit.

Performed at every patient care unit before the area is prepared for the next patient.

Reasons for Terminal Cleaning of the Patient Care Unit.

Prevention of the spread of microorganisms.

Removal of encrusted secretions from framework or bedside rails.

Removal of residue of body wastes from the mattress.

Deodorizing of the bed frame, mattress, and pillow.

Guidelines for Terminal Cleaning.

Review ward SOP for specific procedures.

Use only authorized disinfectant/detergent or germicidal solution for cleaning.

Check to ensure the bedside cabinet is cleared of any valuables belonging to the patient.

Check bed linens for personal items (dentures, contact lenses, money, jewelry, etc.) belonging to the patient.

Prevent spread of microorganisms by carefully removing linen from the bed.

Use caution when cleaning the underframe and bedsprings.

Replace any torn mattress or pillow covers.

Allow the mattress and pillow to air-dry thoroughly before remaking the bed.

2-7. RULES FOR USE OF DISPOSABLE OR NONREUSABLE ITEMS

Do not attempt to reuse (for another patient) or resterilize disposables.

Sterile disposables are considered sterile providing the wrapper is not broken or torn or the expiration date has not passed.

Sterile disposables with torn or broken wrappers must be discarded.

Use disposables for the specific purpose(s) for which they were designed.

Follow manufacturer's directions when using disposables.

Advanced Principles of Patient Hygiene

3-1. INTRODUCTION

Providing for a patient's hygiene is probably the most basic of all nursing care activities, but it is undoubtedly one of the most important. Not only is it a provision for the patient's physical needs; it also contributes immeasurably to the patient's feeling of emotional well-being.

3-2. PURPOSE OF THE PATIENT'S DAILY BATH

Removal of bacteria from the skin.

Confinement in bed increases perspiration, and bacterial growth is stimulated by moisture.

Skin irritation from hospital bed linens may result in skin breakdown and subsequent infection.

Relaxation effect on the patient.

Stimulation of blood circulation to the skin, respirations, and elimination.

Maintenance of joint mobility.

Improvement of the patient's self-image and emotional and mental well-being.

Providing the nurse with an opportunity for health teaching and assessment.

Providing the nurse with an opportunity to give the patient psychological support.

The process of building rapport may begin during the initial bath.

The bath aids in the development of the therapeutic nurse-patient relationship as the patient has the nurse's undivided attention.

3-3. PHYSICAL CONDITIONS WHICH ENCOURAGE SKIN BREAKDOWN IN A PATIENT WHO IS CONFINED TO BED

Immobility. Continuous pressure over any body part impairs circulation to that part and can cause breakdown and eventual ulcerations.

Incontinence. If the patient is unable to control the bladder or bowel functions, skin breakdown is likely to occur due to the presence of moisture and bacteria on the skin.

Emaciation. An emaciated patient may be prone to skin breakdown over bony prominence (heels, elbows, and coccyx).

Obesity. An obese patient may have many skin folds where perspiration and bacteria may contribute to skin breakdown.

Age-Related Skin Changes. An older person's skin is very thin and inelastic. The sweat and oil glands are less active. Thin, dry skin is more susceptible to pressure areas and skin breakdown.

Any Disease or Condition that Affects Circulation. Any disease or condition that affects circulation can encourage skin breakdown in a patient who is confined to bed.

3-4. NURSING INTERVENTION TO PREVENT SKIN BREAKDOWN

The time of the patient's bath or back massage is the most logical time to thoroughly observe the patient's skin for pressure areas.

At the first sign of redness, the area should be washed with soap and water and rubbed with lotion; measures should then be taken to keep the patient off the reddened area.

Report any signs of pressure to the charge nurse.

Keep sheets under the patient clean, smooth, and tight to help eliminate skin irritation.

Ensure adequate nutrition and fluid intake, according to physician's orders.

Every effort should be made to keep urine and feces off the patient's skin, washing the skin with soap and water and keeping the buttocks and genital area dry (lotion or powder may be used depending upon the patient's skin type) when the patient is incontinent.

Obese patients may need assistance washing and drying areas under skin folds (groin, buttocks, under breasts, and so forth.)

For the patient with very dry skin, various bath oils may be added to the bath water.

Soap may be omitted because of its drying effect.

Lotions and oils may be used after the bath.

3-5. TIMING OF PATIENT HYGIENE PROCEDURES

A patient's bath may be given at any time, according to the patient's needs, but certain routines are generally followed on a ward.

Morning Care.

The procedure followed in the morning affects the patient's comfort throughout the day.

Each morning before breakfast, the patient should be assisted to the bathroom, or a bedpan or urinal should be provided, according to the patient's activity level.

The patient is then given the opportunity to wash his/her hands and face and brush his/her teeth. The bed linen is straightened, and the overbed table is cleaned in preparation for the breakfast tray.

After breakfast, the patient has a complete bath (type is dependent upon the patient's condition and mobility), mouth care, a change of clothing, and a back massage.

Bed linens are changed; and the unit is cleaned and straightened to provide a comfortable and safe environment for the patient.

Evening Care.

The care the patient receives at the end of the day greatly influences the patient's level of relaxation and ability to sleep.

An opportunity is provided for elimination; the patient's hands and face are washed; the teeth are brushed; a back rub is given.

Bed linens are straightened; the patient's unit is straightened to ensure comfort and safety. It is important that there are no items, which the patient could slip on, or fall over, such as chairs or linens, on the floor.

3-6. PROVIDING FOR SELECTED PATIENT NEEDS WHILE BATHING A PATIENT

Safety.

The bed may be in the high position during the patient's bed bath, but should be placed in the low position upon completion.

The side rails should be up after the patient's bath for the patient who is confined to the bed.

Side rails help to prevent falls for the elderly patient or the patient who is confused or has a decreased level of consciousness.

The legal aspect requires diligence on the part of nursing personnel.

The patient's call light should be within easy reach to prevent the need to reach for it and risk falling out of bed and to provide easy access in case of pain or distress.

Fire safety in the patient care area calls for the following rules:

No smoking in bed.

No smoking if oxygen is in use.

Always wash your hands before entering and upon leaving the patient's room.

Privacy.

Respect for the patient's privacy decreases the patient's emotional discomfort during personal care.

Keep the door to the patient's room closed.

Pull the curtains around the unit and drape the patient's body during care.

Allow the patient to complete as much personal care as possible; self-care is appropriate and provides additional privacy.

Comfort.

Ensure a comfortable temperature in the patient's room.

Close any windows and the door to the patient's room to prevent drafts and chilling.

Drape the patient appropriately during the bath.

For a bedside bath, maintain bath water between 110oF and 115oF; change the water as it cools and/or gets soapy.

3-7. SIGNIFICANT NURSING OBSERVATIONS DURING THE BATHING PROCEDURE

Physical Observations.

Observe the skin under good, natural light.

Any abnormal skin condition should be described as to its location, color, and size and how it feels to the patient.

The following skin observations should be checked upon admission and daily thereafter:

Cleanliness.

Odor. May be caused by sweat secreted by the sweat glands; by abnormal conditions, such as infection or kidney disease; or by bodily discharges (urine, feces) that need to be cleaned.

Texture. Smooth and elastic or dry and rough; nutritional deficiencies can influence skin texture.

Color. Reddened areas that could indicate pressure, cyanosis (bluish tinge) or jaundice (yellowish tinge).

Temperature. Hot skin could mean fever; cold skin could mean poor circulation.

Sensitivity. Pain, tenderness, itching, or burning.

Swelling (edema). Stretched or tight appearing; usually begins in the ankles or legs or any other dependent part; may be associated with injury.

Skin lesions. Rashes, growths, or breaks in the skin.

Observations may begin at the head (scalp) and proceed to the feet in a systematic manner.

Psychosocial Observations.

Problems in this area may be related to the patient's present problems.

The time of the patient's bath may be a good time to find out more about the patient's psychosocial needs.

Remember that the patient's nonverbal communication may tell you much about the way he/she is feeling.

Oral Care Supplies

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF MOUTH CARE

Purposes.

Provide oral care of the teeth, gums, and mouth.

Remove offensive odors and food debris.

Promote patient comfort and a feeling of well-being.

Preserve the integrity and hydration of the oral mucosa and lips.

Alleviate pain and discomfort, thereby enhancing oral intake.

General Guidelines.

Oral hygiene should be performed before breakfast, after each meal, and at bedtime.

Oral hygiene is especially important for patients receiving oxygen therapy, patients who have nasogastric tubes, and patients who are NPO. Their oral mucosa dries out much faster than normal due to their mouth-breathing.

You should provide for patient privacy during the procedure, as this is an extremely personal procedure for most patients.

Oral care for the unconscious patient should be performed at least every four hours.

Lipstick, chap stick, or vaseline may be applied to the lips to keep them from drying out.

Nursing Records. Nursing observations for the patient's mouth should be recorded in the clinical record, noting such factors as:

Bleeding.

Swelling of gums.

Unusual mouth odor.

Effect of brushing the teeth. Note if there is bleeding when you brush the patient's gums and teeth.

Conscious Patients with Dentures.

General considerations.

Many patients are sensitive or embarrassed about wearing dentures; therefore, the patient's privacy should be respected when the dentures are cleaned.

Dentures must be handled carefully; they are fragile and expensive, and the patient is handicapped without them.

If the dentures are left out of the mouth for any period of time, place them in a covered opaque container with the patient's name on the container.

Dentures must be kept in water to preserve their fit and general quality; the color may change if they become dry.

You may avoid breaking the dentures while cleaning them by holding them over a basin of water with a washcloth folded in the bottom.

Dentures are brushed in the same way as natural teeth; be sure to rinse them well.

The denture cup should be labeled with the patient's name and room number.

Never use hot water to rinse the dentures as it could warp them; use cool or lukewarm water.

The patient's gums and soft tissues should be cared for at least twice per day while the dentures are out of the mouth; a soft-bristled toothbrush, swab, or gauze-covered tongue blade dipped in mouthwash should be used to cleanse the gums, tongue, and soft tissues.

Patients With Mouth Complications. The following problems are common in patients receiving chemotherapy and radiation therapy:

Bleeding.

Observe the patient's mouth frequently for the amount of bleeding present and the specific areas.

Do not floss the patient's teeth; use a Water-pik®.

Brush the teeth and clean the mouth using one of the following methods:

1 Brush the teeth carefully with a very soft toothbrush.

2 Wrap a tongue blade with a gauze sponge saturated with a prescribed solution; carefully swab the teeth and mouth. Do not use lemon/glycerine swabs or commercial mouthwash because they contain alcohol, which causes burning.

Infection.

Observe the patient's mouth for appearance, integrity, and general condition.

Wear clean gloves during the procedure.

Obtain a culture, if ordered.

Do not floss the teeth if the mouth is irritated or painful.

Assist the patient with brushing the teeth and cleaning the mouth, using a soft toothbrush or a gauze-padded tongue blade.

Rinse the mouth with water and the prescribed solution, if ordered.

Ulcerations, to include stomatitis.

Basic procedure for the patient with an infection should be followed.

If the patient's mouth is extremely painful, rinsing the mouth with a local anesthetic, as prescribed by a physician, may be necessary.

Mouthwash and other solutions which contain alcohol should not be used for the patient with ulcerations as they are frequently very painful.

Unconscious Patients.

Oral care should be performed at least every four hours.

Oral suctioning may be required for the unconscious patient to prevent aspiration.

A soft toothbrush or gauze-padded tongue blade may be used to clean the teeth and mouth.

The patient should be positioned in the lateral position with the head turned toward the side to provide for drainage and to prevent aspiration.

Advanced Principles of Patient Hygiene

3-9. BACK MASSAGE AS A PATIENT COMFORT MEASURE

Decreases muscle tension and promotes relaxation.

Increases circulation to the area.

Aids in the development of the therapeutic nurse-patient relationship.

3-10. BASIC PRINCIPLES OF BACK MASSAGE

The psychological benefits of back massage cannot be overstressed for the hospitalized patient. The following statements illustrate the concept of therapeutic touch as an integral part of the domain of nursing.

Back Massage

Touch can be perceived as a manifestation of caring and communication between the nurse and the patient.

Tactile communication between healthy and ill individuals can have highly beneficial results.

Therapeutic touch may make some patients uncomfortable; you are entering their personal space and their feelings must be respected, so make sure you ask the patient if he/she would like a back rub.

Agents used for back massage:

Lotions or emollients.

Lotions and emollients reduce friction and lubricate the skin.

They are appropriate for most patients, especially those with a tendency toward dry skin; that is, elderly patients.

Massage Oil

Rubbing alcohol.

Alcohol evaporates quickly, so it has a cooling but very drying effect.

A certain amount of alcohol is absorbed by the skin so it should not be used on infants, elderly patients, or patients with liver disease.

Powder.

Powder reduces friction but also has a drying effect on the skin.

It may be appropriate for those patients who perspire freely and/or are confined to bed.

General guidelines.

A back massage should take about five to ten minutes and can be given with the patient's bath, before bedtime, or at any other time during the day.

Determine if any patient allergies or skin sensitivities exist before applying lotion to the patient's skin.

The greatest relaxation effect of a massage occurs when the rhythm of the massage is coordinated with the patient's breathing.

3-11. GUIDELINES FOR SHAVING A MALE PATIENT

If the patient is alert, question him about his shaving habits, and follow his routine as closely as possible.

Gather equipment and supplies.

Towels.

Washcloth.

Basin with hot water.

Shaving cream.

Razor.

Soap.

Aftershave lotion.

Wet the wash cloth, wring out any excess moisture, and apply it to the beard area (to soften the beard).

Apply shaving cream to the beard.

Shave the beard on the cheeks and upper lip in the direction that the hair grows.

Shave the beard on the neck against the direction of the hair growth.

Wash off any remaining shaving cream.

With clean water, finish washing the patient's face.

Always use an electric razor on patients with bleeding disorders to prevent uncontrollable bleeding from facial cuts.

Do not use plugged in electric razors on patients who are receiving oxygen therapy because of the danger of combustion; safety razors or rechargeable battery operated shavers are safe.

Consult with the charge nurse before shaving any patient who has had facial surgery or who may have hemophilia.

Patients who are combative, suicidal, or disoriented should have supervision and assistance while shaving.

3-12. PERINEAL CARE

Perineal care is often referred to as "pericare;" it consists of external irrigation of the vulva and perineum following voiding or defecation and is part of the routine A. M. and P. M. care. Patients may be able to perform their own perineal care or may need partial or total assistance from the nurse. Embarrassment on the part of the patient and the nurse can be effectively dealt with by ensuring patient privacy during the procedure and not totally exposing the patient's genital area.

Key points:

Ensure patient privacy.

Wipe from front to back (vagina toward rectum) on female patients to avoid contaminating the vagina or urethral meatus.

Do not use the same washcloth for any other portion of the patient's bath.

3-13. BED PATIENT'S HAIR CARE

Principles for Shampooing the Bed Patient's Hair.

The supine position is preferred for weaker patients.

Patients with significant heart or lung disease will not tolerate being supine; they must be in a sitting position.

Hair care should be given regularly during illness, just as it would be normally.

Purposes of Hair Care.

Hair care improves the morale of the patient.

It stimulates the circulation of the scalp.

Shampooing removes bacteria, microorganisms, oils, and dirt that cling to the hair.

3-14. CLOSING.

Nothing points out loss of independence quite as much as an inability to perform personal hygiene unassisted. Your thoughtfulness and the professionalism you exhibit when assisting a patient with hygiene needs will foster that patient's feelings of independence, confidence, trust, and comfort.

Body Mechanics

SECTION I. Techniques of Body Mechanics

4-1. INTRODUCTION

Some of the most common injuries sustained by members of the health care team are severe musculoskeletal strains. Many injuries can be avoided by the conscious use of proper body mechanics when performing physical labor.

4-2. DEFINITION

Body mechanics is the utilization of correct muscles to complete a task safely and efficiently, without undue strain on any muscle or joint.

4-3. PRINCIPLES OF GOOD BODY MECHANICS

Maintain a Stable Center of Gravity.

Keep your center of gravity low.

Keep your back straight.

Bend at the knees and hips.

Maintain a Wide Base of Support. This will provide you with maximum stability while lifting.

Keep your feet apart.

Place one foot slightly ahead of the other.

Flex your knees to absorb jolts.

Turn with your feet.

Maintain the Line of Gravity. The line should pass vertically through the base of support.

Keep your back straight.

Keep the object being lifted close to your body.

Maintain Proper Body Alignment.

Tuck in your buttocks.

Pull your abdomen in and up.

Keep your back flat.

Keep your head up.

Keep your chin in.

Keep your weight forward and supported on the outside of your feet.

4-4. TECHNIQUES OF BODY MECHANICS

Lifting.

Use the stronger leg muscles for lifting.

Bend at the knees and hips; keep your back straight.

Lift straight upward, in one smooth motion.

Reaching.

Stand directly in front of and close to the object.

Avoid twisting or stretching.

Use a stool or ladder for high objects.

Maintain a good balance and a firm base of support.

Before moving the object, be sure that it is not too large or too heavy.

Pivoting.

Place one foot slightly ahead of the other.

Turn both feet at the same time, pivoting on the heel of one foot and the toe of the other.

Maintain a good center of gravity while holding or carrying the object.

Avoid Stooping.

Squat (bending at the hips and knees).

Avoid stooping (bending at the waist).

Use your leg muscles to return to an upright position.

4-5. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR PERFORMING PHYSICAL TASKS

It is easier to pull, push, or roll an object than it is to lift it.

Movements should be smooth and coordinated rather than jerky.

Less energy or force is required to keep an object moving than it is to start and stop it.

Use the arm and leg muscles as much as possible, the back muscles as little as possible.

Keep the work as close as possible to your body. It puts less of a strain on your back, legs, and arms.

Rock backward or forward on your feet to use your body weight as a pushing or pulling force.

Keep the work at a comfortable height to avoid excessive bending at the waist.

Keep your body in good physical condition to reduce the chance of injury.

4-6. REASONS FOR THE USE OF PROPER BODY MECHANICS

Use proper body mechanics in order to avoid the following:

Excessive fatigue.

Muscle strains or tears.

Skeletal injuries.

Injury to the patient.

Injury to assisting staff members.

4-7. STEPS INVOLVED IN PROPERLY MOVING AN OBJECT TO A NEW LOCATION

The following paragraph takes you through the process of moving (lifting, pivoting, squatting, and carrying) a heavy object. (The same rules would apply to moving a patient.) The object will be moved from a waist high area to a lower area five to ten feet away. The procedure will combine all the rules of body mechanics previously discussed.

Identify the object to be moved.

Adopt a stable base of support.

Your feet are separated.

One foot is behind the other.

Your back is straight.

Grasp the object at its approximate center of gravity.

Pull the object toward your body's center of gravity using your arm and leg muscles.

Re-establish your base of support and appropriate body alignment.

Your back is straight.

You have a stable base of support.

You are holding the object approximately at waist height and close to your body.

Pivot toward the desired direction of travel.

Turn on both feet at the same time.

Maintain a stable balance.

Re-establish a stable base of support and appropriate body alignment.

Your back is straight.

Your feet are apart, one slightly behind the other.

The object is at hip level, close to your body.

Squat and place the object onto the lower area.

Bend at the knees and hips.

Maintain a straight back.

Maintain a stable base of support.

Use your arm and leg muscles (as needed) for guidance.

Use your leg muscles to resume an upright position.

Body Mechanics

SECTION II. Positioning and Ambulating the Adult Patient

4-8. INTRODUCTION

One of the basic procedures that nursing personnel perform most frequently is that of changing the patient's position. Any position, even the most comfortable one, will become unbearable after a period of time. Whereas the healthy person has the ability to move at will, the sick person's movements may be limited by disease, injury, or helplessness. It is often the responsibility of the practical nurse to position the patient and change his position frequently. Once the patient is able to ambulate, certain precautions must be taken to ensure the patient's safety.

4-9. REASONS FOR CHANGING THE POSITION OF A PATIENT

The following are reasons for changing a patient's position.

To promote comfort and relaxation.

To restore body function.

Changing positions improves gastrointestinal function.

It also improves respiratory function.

Changing positions allows for greater lung expansion.

It relieves pressure on the diaphragm.

To prevent deformities.

When one lies in bed for long periods of time, muscles become atonic and atrophy.

Prevention of deformities will allow the patient to ambulate when his activity level is advanced.

To relieve pressure and prevent strain (which lead to the formation of decubiti).

To stimulate circulation.

To give treatments (that is), range of motion exercises).

4-10. BASIC PRINCIPLES IN POSITIONING OF PATIENTS

Maintain good patient body alignment. Think of the patient in bed as though he were standing.

Maintain the patient's safety.

Reassure the patient to promote comfort and cooperation.

Properly handle the patient's body to prevent pain or injury.

Keep in mind proper body mechanics for the practical nurse.

Obtain assistance, if needed, to move heavy or helpless patients.

Follow specific physician's orders. A physician's order, such as one of the following, is needed for the patient to be out of bed.

"Up ad lib."

"Up as desired."

"OOB" (out of bed).

Do not use special devices (that is., splints, traction) unless ordered. Ask if you do not know what is allowed.

4-11. TURNING THE ADULT PATIENT

a. General Principles for Turning the Adult Patient.

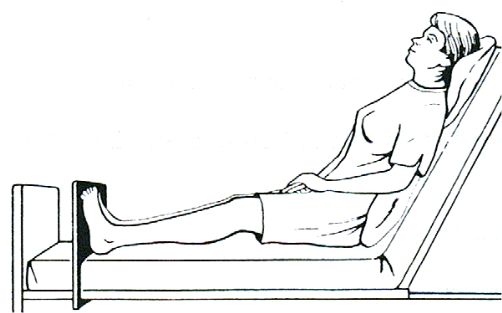

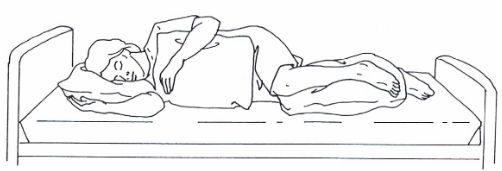

Sometimes the physician will specify how often to turn a patient. A schedule can be set up for turning the adult patient throughout his "awake" hours. The patient should be rotated through four positions (unless a particular position is contraindicated):

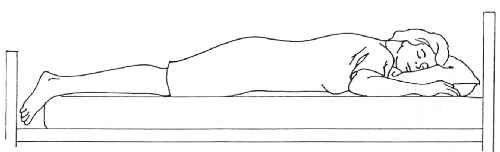

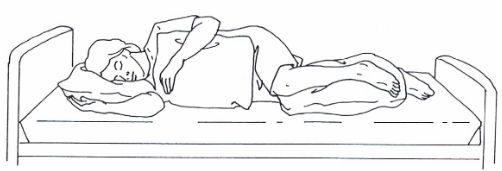

Prone (see figure 4-1 and section 4-13).

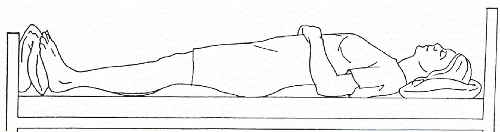

Supine (figure 4-2 and section 4-13).

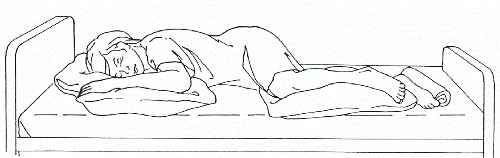

Left Sim's (figure 4-3).

Right Sim's (figure 4-3).

Plan a schedule and follow it. Record the position change each time to ensure that all positions are used.

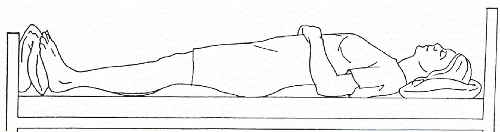

Figure 4-1. Prone position.

Figure 4-2. Supine position.

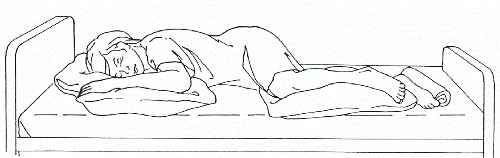

Figure 4-3. Sim’s position.

One example of a schedule for turning would be:

1000-- Prone position

1200--Left Sim's position

1400--Supine position

1600--Right Sim's position

1800--Prone position

Notice that in the preceding sequence, the patient is required to make only a quarter turn rather than a half turn each time the position is changed. If the patient experiences pain while turning, a quarter turn will be less painful than a half turn.

Certain conditions may make it impossible to turn the patient. Turning may be impossible if the patient has fractures that require traction appliances. Turning may be harmful to patients with spinal injuries. In these cases, you need to rub the back by lifting the patient slightly off the bed and massaging with your hand held flat. It is especially important to prevent skin breakdowns in the person who lies on his back for long periods of time.

NOTE: For the initial development of skin breakdown, a patient does not have to lie on his back for long periods of time, especially if moisture and sheet wrinkles are present.

You may want to turn a patient only to wash or rub the back or change the bed.

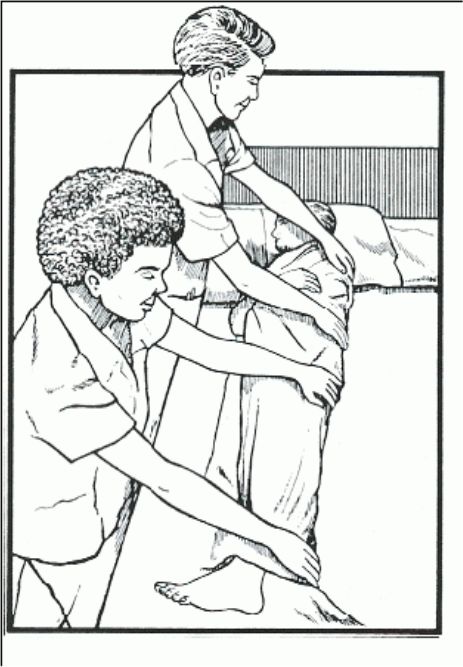

Figure 4-4. Logrolling.

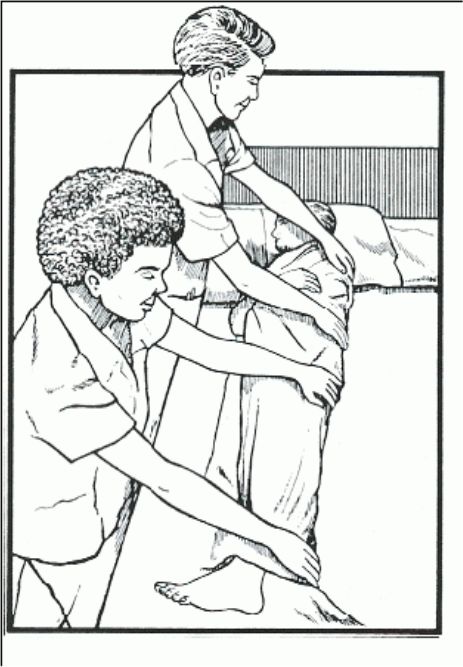

Logrolling (see figure 4-4).

Description.

Logrolling is a technique used to turn a patient whose body must at all times be kept in a straight alignment (like a log).

This technique is used for the patient who has a spinal injury.

Logrolling is used for the patient who must be turned in one movement, without twisting.

Logrolling requires two people, or if the patient is large, three people.

Technique.

Wash your hands.

Approach and identify the patient (by checking the identification band) and explain the procedure (using simple terms and pointing out the benefits).

Provide privacy.

Position the bed.

The bed should be in the flat position at a comfortable working height.

Lower the side rail on the side of the body at which you are working.

Position yourself with your feet apart and your knees flexed close to the side of the bed.

Fold the patient's arms across his chest.

Place your arms under the patient so that a major portion of the patient's weight is centered between your arms. The arm of one nurse should support the patient's head and neck.

On the count of three, move the patient to the side of the bed, rocking backward on your heels and keeping the patient's body in correct alignment.

Raise the side rail on that side of the bed.

Move to the other side of the bed.

Place a pillow under the patient's head and another between his legs.

Position the patient's near arm toward you.

Grasp the far side of the patient's body with your hands evenly distributed from the shoulder to the thigh.

On the count of three, roll the patient to a lateral position, rocking backward onto your heels.

Place pillows in front of and behind the patient's trunk to support his alignment in the lateral position.

Provide for the patient's comfort and safety.

1 Position the call bell.

2 Place personal items within reach.

3 Be sure the side rails are up and secure.

Report and record as appropriate.

4-12. MAINTAINING PROPER BODY ALIGNMENT WITH THE PATIENT ON HIS BACK

Patients who must lie on their backs much of the time should be kept as comfortable as possible to prevent body deformities. The paraplegic and quadriplegic may not be able to tell you if their position is uncomfortable. You must be especially attentive in this case to prevent possible problems from malalignment.

Pillows can be used to support the patient's head, neck, arms, and hands and a footboard used to support the feet.

Proper alignment gives respiratory and digestive organs room to function normally.

The footboard is slanted to support the feet at right angles to the leg (a normal angle) and prevent foot drop.

If the patient's trunk must lie flatter than the neck and head:

The patient should have only one pillow to support the head and neck.

The patient may have a pillow placed under the legs to prevent pressure on the heels.

Body Mechanics

SECTION II. Positioning and Ambulating the Adult Patient

4-13. COMMON POSITIONS UTILIZED FOR THE ADULT PATIENT

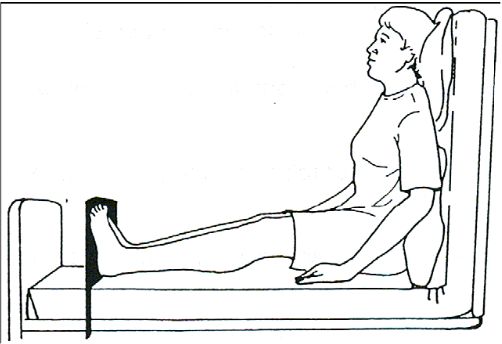

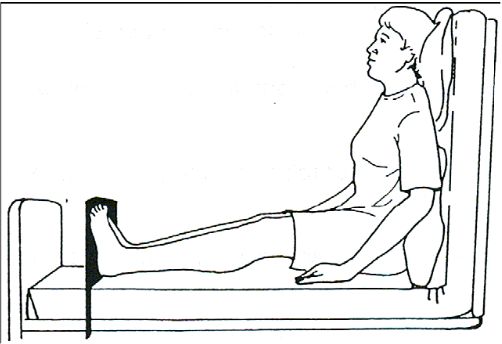

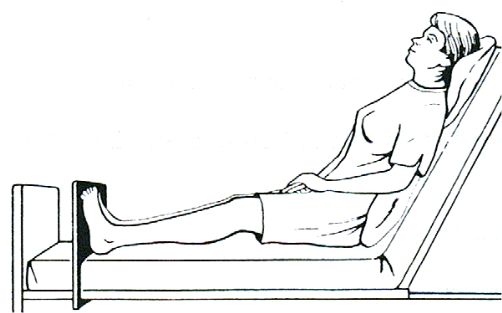

Placing the Adult Patient in the Supine Position (see figure 4-2).

Collect equipment.

Pillows.

Positioning aids as indicated.

Wash your hands.

Approach and identify the patient (by checking the identification band) and explain the procedure (using simple terms and pointing out the benefits).

Provide privacy throughout the procedure.

Position the bed.

Place the bed in a flat or level position at working height, unless contraindicated.

Lower the side rails on the proximal side (as necessary).

Move the patient from a lateral (side) position to a supine position.

For the patient on his side, remove supportive pillows.

Fold top bedding back to the hips, being careful to avoid any undue exposure of the patient's body.

With one hand on the patient's shoulder and one on the hip, roll his body in one piece (like a log) over onto his back.

Align the patient's body in good position.

Head, neck, and spine are in a straight line.