SINCE ITS EMERGENCE in the early 1980s, HIV infection in the United States has evolved from an acute debilitating condition to a chronic, treatable illness. Patients with HIV infection are at risk for various comorbidities and adverse reactions associated with long-term medication administration, as well as disorders associated with normal aging and chronic HIV infection.

Because HIV infection is seen in every age group and can cause multisystem disease, you're likely to care for patients with HIV infection across all settings. This article provides an update on HIV infection assessment and treatment, and discusses how you can help your patients manage this chronic disease.

Global problem

An estimated 33.4 million people throughout the world are living with HIV infection.1 Two-thirds of these people can be found in sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for 22.4 million people living with HIV. In contrast, approximately 1.1 million adults and adolescents in the United States are living with HIV infection or AIDS (the most serious stage of HIV infection)

The estimated number of people with HIV infection or AIDS has increased because treatment advances have significantly prolonged the lives of people with HIV. Each year, approximately 56,000 people in the United States are newly infected with HIV. With increased public awareness of the effects of HIV infection and the simple strategy of using a latex condom to prevent HIV transmission, the infection rate should, ideally, be going down. Various social, cultural, biological, political, and even financial factors help explain why HIV transmission continues to occur at such an alarming rate.

Screening for HIV infection

Of the 1.1 million Americans with HIV infection, an estimated 21% are unaware they're infected.2,3 These people account for 54% to 70% of newly transmitted infections.4,5 Transmission risk behaviors decrease among people who are aware of their HIV status, so knowing one's status can be an important prevention strategy.

The CDC recommends that all people between ages 13 and 64 be screened for HIV infection as a routine part of healthcare, regardless of their risk.2 Annual screening is recommended for individuals who are at continued risk for HIV infections, such as those who continue to inject illicit drugs or engage in unprotected sexual intercourse.

Patients can be screened for HIV infection during a routine healthcare visit, along with screenings for dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes. Because not all Americans receive routine healthcare, the CDC also recommends routine HIV infection testing in acute care hospitals and EDs. The percentage of patients who test positive for HIV infection in hospitals and EDs (2% to 7%) exceeds that seen nationally at publicly funded HIV counseling and testing sites (1.5%) and STD clinics (2%) that treat people at high risk for HIV.2 Testing for HIV infection is easily done in most any setting (see HIV testing and results in 20 minutes). Testing staff must be aware of applicable state laws that may or may not include requirements for pretest counseling, written consent, and posttest counseling.

For specific state requirements, you can find a useful guideline at http://www.nccc.ucsf.edu/docs/quickstatelawguidelines.pdf.

Refining treatment options

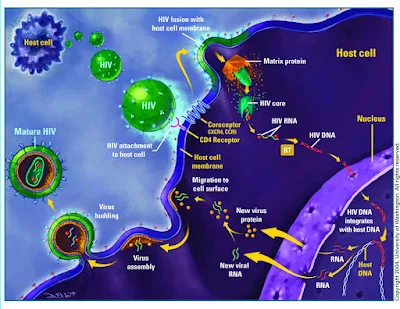

Since 1996, HIV infection treatment has focused on combining drugs from different HIV drug classes. A combination of drugs from at least two anti-HIV drug classes provides the best long-term clinical outcomes. Currently 6 different anti-HIV drug classes, 22 unique drugs, and 6 combination tablets are available (see Common drugs used to treat HIV).

The decision to begin anti-HIV therapy, or what's commonly called antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, in patients with HIV infection is based primarily on the patient's CD4 cell count. The CD4 cell count is a key marker of immune system health in patients with HIV infection. The lower the count, the more damage HIV has done. Anyone with a CD4 cell count less than 200 T-lymphocytes/mm3, or a CD4 T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of less than 14, is considered to have AIDS.8 Without treatment, people with AIDS are at higher risk for AIDS-related illnesses commonly known as opportunistic diseases. Because the immune system is weakened in people with AIDS, some of these illnesses can be life-threatening.

ARV therapy is usually given to patients with a history of an AIDS-defining illness (an illness that's generally seen in patients with a weakened immune system, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and Kaposi sarcoma); a CD4 cell count under 350 cells/mm3; HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN); hepatitis B virus (HBV) coinfection; or women with HIV who are pregnant.

Current guidelines also recommend starting ARV therapy if the CD4 cell count is less than 500 cells/mm3.8 For patients with CD4 cell counts over 500 cells/mm3, starting ARV therapy is considered optional because of the lack of any conclusive clinical studies that demonstrate a clinical benefit (such as a reduction in mortality or new cancers) at this stage.8 The current recommended HIV therapy in patients who've never been on therapy (treatment-naive patients) is a regimen of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine combined with one of the following: efavirenz; atazanavir with ritonavir; darunavir with ritonavir; or raltegravir with ritonavir.8 Each of these combinations has been shown, in randomized controlled trials, to fully suppress viral replication, avoid the development of HIV medication resistance, and adequately increase the patient's CD4 cell count when compared with other drug combinations. These regimens are also preferred because they're usually well tolerated with few adverse reactions, and with the exception of raltegravir, all of the regimens can be administered once a day. In addition to these benefits, the regimen of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine plus efavirenz has been combined into one pill that can be taken once a day. Combining drugs into one pill decreases the patient's "pill burden," reducing the complexity of therapy, and may improve adherence to therapy.

Before patients are started on a new ARV regimen, assess their readiness (see Is your patient ready for ARV therapy?). Therapy with these medications is lifelong, and once started, generally continues without interruption. Teach patients that these medications must be taken exactly as prescribed. If they miss doses, the virus can become resistant to the medication, rendering the therapy ineffective. A virus that's resistant to one drug in a class can become resistant to other drugs in the same class, limiting the number of drugs available for treating the patient.

All ARV medications cause adverse reactions; without proper education, patients who experience unpleasant reactions may discontinue their medication. For example, most patients who take efavirenz experience vivid hallucinations during sleep or dizziness during the day for the first 2 weeks after taking the drug. To minimize these reactions, teach patients to take this medication at bedtime and advise them to alter their activities until they can work through the period of medication adjustment.

Tell patients to report any adverse reactions they experience to their healthcare provider and stress that they should never stop taking the medication on their own.

Advise patients that their healthcare provider will ask them to return within 2 weeks to evaluate their response to the new regimen. This includes monitoring the patient for such adverse reactions as blood dyscrasias and abnormal serum glucose or lipid levels that can occur with most ARV medications. After 4 to 6 weeks on therapy, the healthcare provider will also order several blood tests to evaluate patient response to therapy.

Treatment goals

The two most important biomarkers of successful response to ARV therapy are the evaluation of the viral load, by measuring serum HIV RNA levels, and the CD4 cell count. The goal of ARV therapy is to achieve a viral load below the limit of detection, which is generally less than 20 to 75 copies of HIV RNA. (The specific value depends on the commercial test that's used; check the manufacturer's instructions.)

The second treatment goal is an increase in CD4 cell count. With effective therapy, patients should have a 50- to 100-cell increase in their CD4 cell counts per year. Many patients who start therapy with CD4 cell counts over 350 and have a good response to therapy can expect to normalize their CD4 cell counts.

Assess patients who don't meet these therapeutic goals for adherence to therapy, drug-drug interactions, and drug resistance.

Long-term problems: It's complicated

0With more effective therapy for HIV infection, the incidence of once-common opportunistic diseases, such as cryptococcus, histoplasmosis, and bacillary angiomatosis, has decreased. But as patients live longer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic renal disease, and cancers that usually aren't seen in patients with AIDS (such as anal and lung cancers) are increasingly common. These complications may be due to a combination of:

* chronic immune system activation triggered by HIV

* ARV medication adverse reactions (as discussed below)

* human papillomavirus (HPV) coinfection

* behavioral factors such as smoking, chronic alcohol abuse, and illicit drug use

* normal age-related changes.

HIV and CVD

HIV infection is a strong risk factor for CVD. An analysis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in a large healthcare system found that the rate of AMI among patients with HIV infection was nearly double that in those without HIV, even after adjusting for age, sex, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia.10 The Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs Study Group demonstrated that subjects had an increased incidence of AMI that was proportionate to the cumulative duration of therapy with ARVs, particularly protease inhibitors (PIs) and the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) abacavir and didanosine. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) weren't linked to a higher incidence of AMI. Newer ARV agents weren't in use at the time of the study.

Conversely, the HIV Out-Patient Study didn't find any association of CVD with any specific ARV agents or classes, but detected a significantly increased association with traditional CVD risk factors.

Compared with people in the general population, a greater proportion of patients with HIV infection have one or more risk factors for CVD (such as smoking, hypertension, or insulin resistance/diabetes) that may cumulatively contribute to higher rates of CVD. HIV treatments may also contribute to CVD because NRTIs, NNRTIs, and PIs are associated with dyslipidemia. How these drugs cause dyslipidemia varies by drug class.

To combat the effect of lipid accumulation, a non-PI-based regimen (such as raltegravir combined with tenofovir and emtricitabine) may be prescribed. If a PI-based regimen is indicated, atazanavir without ritonavir (and combined with two NRTIs) can be used. If the PI must be combined with ritonavir, atazanavir with ritonavir produces less of an increase in low-density lipoprotein and triglycerides than other PIs.

Teach patients about CVD risk reduction strategies that include smoking cessation, diet modification, and physical activity. Monitor the patient's fasting lipid profile at baseline, at 3 to 6 months after starting a new regimen, and then annually or more frequently if indicated (in high-risk patients or in patients with abnormal baseline levels). Generally, if lifestyle or ARV regimen modifications don't achieve lipid goals, adding antidyslipidemic agents to the regimen is considered. When using antidyslipidemic agents in HIV-infected patients, it's important to consider potential drug-drug interactions with ARVs. For example, certain statins such as simvastatin and lovastatin are contraindicated with PIs due to a serious drug-drug interaction.

HIV and renal disease

HIV infection is associated with several renal syndromes, including chronic renal failure. Renal disease linked to HIV infection includes thrombotic microangiopathic renal diseases, immune-mediated glomerulonephritis, and HIVAN.

Kidney function is abnormal in up to 30% of HIV-infected patients.13 The most common complication is HIVAN, a disease characterized by massive nephrotic proteinuria (often more than 10 g/day), the absence of edema, and large echogenic kidneys seen on ultrasound. If left untreated, HIVAN can progress to renal failure in 1 to 2 years. HIVAN is almost always seen in patients with advanced immunosuppression (a CD4 cell count under 100).

HIV medications can also cause renal dysfunction. Indinavir (rarely used today) and atazanavir may cause nephrolithiasis. Tenofovir, the most widely prescribed NRTI and the preferred drug in treatment-naive patients, can cause tubular injury that leads to renal tubular dysfunction and a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR).Studies have shown only minimal decreases in the GFR of patients taking tenofovir and a low incidence (0.3%) of renal failure. Because patients may have concurrent illnesses that may affect the kidneys (such as dehydration), it's hard to be certain that any one drug alone is responsible for renal disease.

Minor lab abnormalities are also associated with tenofovir. Fanconi syndrome, which causes phosphate wasting along with renal losses of potassium, bicarbonate, uric acid, amino acids, and glucose, can be reversed with discontinuation of the drug. Patients with diabetes mellitus or hypertension, a GFR less than 90 mL/minute/1.73 m2, and who receive medications excreted renally or PIs in combination with ritonavir (a "boosted" PI) should undergo biannual renal function and serum phosphorus testing and urinalysis while taking tenofovir.13 Due to the potential renal toxicity with tenofovir, use this drug with caution if your patient has baseline renal insufficiency or other risk factors for renal dysfunction (hypertension, diabetes, older age).

Monitor patients for abnormalities in glucose metabolism or hypertension, which are common risk factors for renal disease. Work with patients to help them meet treatment goals. When patients experience gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms such as diarrhea or vomiting, advise them to drink plenty of water to prevent dehydration, which may result in acute kidney injury.

Many drugs administered as part of treatment or used to prevent opportunistic infection (such as trimethroprim/sulfamethoxale for P. jiroveci prevention) are nephrotoxic. Screen for changes in renal function by calculating the patient's GFR by using either the modified Cockcroft-Gault formula or the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.

HIV and cancer

The early HIV epidemic was defined by malignancies such as Kaposi sarcoma and central nervous system lymphomas. The incidence of these two AIDS-defining malignancies (ADMs) has declined dramatically. Today, non-AIDS-defining malignancies (non-ADMs) are more common than ADMs, and the risk of both types is higher for patients with lower CD4 cell counts. The four most frequently reported fatal non-ADMs are lung cancer (20%); cancer of the GI tract, such as gastric or hepatocellular carcinomas (13%) and anal cancer (7%); and cancers of the hematologic system, such as Hodgkin lymphoma (7%). The increased incidence of non-ADMs may be related to the fact that HIV-infected patients, either due to their lifestyle or other circumstances, are more subject to the traditional risk factors than non-HIV patients. For example, the rates of smoking in those with HIV infection far exceed the rates of smoking in the general population.12 The incidence of anal cancers is increased in HIV-positive men who have sex with men; there's a 60-fold increase in the relative risk increase of anal neoplasia in this population when compared with the general population.

In general, patients with HIV infection receive age-appropriate cancer screenings according to the same guidelines as noninfected patients. The greatest difference is screening for anal cancer.

Anal cancer is rare in the United States, with an incidence of 1 per 100,000 in the general population. In contrast, the risk of anal cancer for women and men of all ages with HIV infection is 6.8 per 100,000-37 times greater than that in their respective general populations.

HPV causes anal cancer. (See "HPV-Related Cancer: An Equal Opportunity Danger" in the October issue of Nursing2010.) Patients with HIV disease are at higher risk for developing anal cancer because HIV infection attenuates the host response to HPV infection. Patients with low CD4 cell counts have a higher incidence of persistent HPV infection and greater incidence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN), changes in the anal canal that are precursors to invasive anal cancer.20 AIN grades 1, 2, and 3 reflect low-, moderate-, and high-grade dysplasia. Grades 2 and 3 are often grouped together as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and associated with a higher risk of invasive cancer.

Annual anal cancer screenings are recommended for HIV-infected men with a history of sex with other men, HIV-infected women with a history of cervical or vulvar dysplasia (because HPV is associated with these cancers too), and anyone with a history of anogenital condyloma. Anal cancer screening may include an anal Pap test or anoscopy. An anal Pap test is the same type of test used to screen women for cervical cancer.

Anoscopy is the endoscopic evaluation of the anus, anal canal, and lower rectum. Anyone with an abnormal anal Pap test should have a follow-up anoscopy.

Assess patients' sexual history for risk factors that put them in the high-risk category to ensure they're appropriately screened for anal cancer. Keep in mind that women with dysplasia on their cervical Pap tests are at high risk for anal dysplasia and should also be screened.

Be prepared

Thanks to the effectiveness of combination ARV therapy, people with HIV infection are living longer than ever. But complications and adverse reactions arising from treatment can affect the patient's quality of life or psychosocial functioning. Advise your patients about what to expect during therapy and carefully monitor them for complications. With your help, patients with HIV infection can live long, productive lives.

HIV TESTING AND RESULTS IN 20 MINUTES

Conventional testing for HIV infection is done via lab analysis of a blood sample, which may delay diagnosis. More rapid testing that produces results in 20 minutes is now available. It's easy to use and doesn't require lab facilities or highly trained staff.

To perform an oral test, place the pad of the device above the patient's teeth along the outer gum and swab once around both the upper and lower gums to collect oral mucosal transudate from the patient's mouth. Insert the device into a vial containing the developing solution.

In 20 minutes, the device indicates whether HIV-1 or HIV-2 antibodies are present. If one line appears on the strip, the person isn't infected with HIV (with 99.8% accuracy). If two lines appear, the patient is likely infected (99.3% accuracy).

If the result is positive, it must be confirmed with additional, more specific tests to detect HIV antibodies.

IS YOUR PATIENT READY FOR ARV THERAPY?

Before starting therapy, assess your patient's:

* basic knowledge of HIV infection, transmission, and prevention

* understanding of ARV treatment and potential adverse reactions

* ability to comprehend, cope, and adhere to the prescribed therapy

* willingness to create support systems to cope with HIV status and facilitate treatment, such as disclosing status to family, friends, and partners.

After starting therapy, assess your patient's:

* advanced knowledge and skills to cope and manage HIV status and treatment

* ability to recognize and seek care for opportunistic diseases and complications.

Evaluate your patient's:

* level of HIV knowledge, personal autonomy, skills, and confidence to manage the consequences of HIV status and treatment

* capacity to take action that encourages health and discourages the determinants of ill health, such as substance abuse and unsafe sexual practices.

Source link...Adapted from: Gebrekristos HT, Mlisana KP, Karim QA. Patients' readiness to start highly active antiretroviral treatment for HIV. BMJ. 2005;331(7519):772-775.

No comments:

Post a Comment